Lincoln Hall Project

A Courtship Revolution, Scholarship, and Dorm Life at Mid-Century

By John Heinz, AB ’57, anthropology

I really enjoyed that scholarly LASNews series on the evolution of education, but maybe that’s just me—an anthropology major. Hey, those were exciting times on campus in the middle of the last century, but you had to have been an anthropologist.

In the 1950s, at Champaign-Urbana, there was quite a revolution in courtship rituals. Playboy magazine began in 1953 as the most popular harbinger, but there was serious paperback reading too, like the cultural comparisons of Margaret Mead. I think that the most popular paperback title poking out from our protective book jackets was a sort of marriage manual for the unmarried: Love without Fear. There was a slender volume of epic poetry called This Is My Beloved, and on LP records we had the penetrating piano ditties of Tom Lehr.

Sororities elected standards officers who tried to sweep back the tide of nature. One episode in the popular film Animal House seems to have been based on an Illinois case—this is the scene where, in a long row of parked cars, the girls are all saying goodnight to their dates. In our real case, an auto erotic couple had been surprised by some fink, and so after an in-house kangaroo court—it’s always the woman who pays—word traveled all over campus about “the case of the girl with the golden arm.” This was in about the year 1350 A.D.—medieval times—and the guilty sister was sentenced to be dragged through the streets and branded.

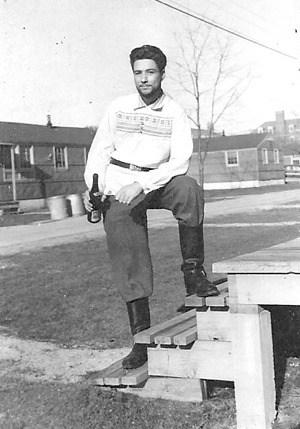

Campus seemed to be a secure and stable place, as enduring as our gothic lane of elm trees. I submit that the social surprise of mid-century came from the United States military, of which I later became a proud part. The good invasion of veterans after WWII brought older and well-traveled voices into our freshman mix. At that time I dwelt in an architect’s anomaly called Noble Dorm. This freshman housing was apparently designed in the late war, because it had few walls and exposed all inhabitants. Noble replaced wooden barracks that were known as the Parade Ground Units.

After the war, some economical architect tried to make Noble more academic by standing up rows of lockers to make rooms of about 12 by 10 feet. Into them the crafty draftsmen drew in two double-deck bunks. In later years I worked in the architectural trade and learned of the constant challenge to squeeze big shapes into little shapes.

I noted to my mother that I was now living in proximity with three upwardly mobile roommates of an exuberant tradition. She noted back: “You can learn a lot from them.”

We dorm dwellers elected floor officers, and so to enforce quiet hours, our floor elected a large veteran. He stated that he had been an M.P. during his service, and he gave an amusing explanation of that acronym. Noble Dorm in practice became what police call a slammer. The locker doors depended upon common sensitivity in use; our quiet officer stayed quiet. But so much was going on that I do not recall any complaints about the slamming.

We discovered that we could dispose of trash, mostly crumpled paper balls, over the locker rows—maybe over two or three rows. Even worse, we would practice imperialism by quietly sliding whole rows of lockers to gain a few precious inches. We loved Noble Dorm; there were no real fights. Someone dashed off a poem and inscribed it on a lampshade; it ended with, “when we get to Heaven, the angels sure will yell, ‘Welcome men of Noble Dorm, you’ve served your term in Hell!’” But we loved it. Although some of the dorm rats were of high income demographics, the noise and the population density were never even spoken of.

One of the Noble veterans, William Field, who had served in Britain, served me as a mentor. I was older than most of the incoming due to community college, and we decided to bid farewell to our good friends, and move to a quiet apartment away from both the men’s housing zone and the women’s housing zone. We were making our own hours, cooking our own meals, and cracking books—but without the permission of University Housing. I was finally able, after some petitioning, to satisfy Housing and score a victory against paternalism. This was about the same time as the movie Mr. Belvedere Goes to College in which the Clifton Webb character, at a certain age, enrolls in a school that requires incoming students to wear odd little hats called “dinks.” He rebels and is written up as, “Thinks dinks stink.”

Our good university, according to a previous article on evolution in education, at one time actually had a freshman dink rule. I thought of the Webb character again, when, after the housing clash, I had to apply for permission to use the rare book department in Norlin Library. This time, I seem to have been not old enough, as rare book use was then for graduate students only. I appealed, because I was writing a paper on Robert Green Ingersoll and his private papers were in that department. My appeal failed, perhaps due to the radical nature of my subject, the arch atheist of Southern Illinois. I might have written something significant on “Honest Bob Ingersoll” but for that other dink rule.

It cannot be easy to be a University administrator, being between Charybdis and the Hellespont—between flaming youth and concerned parents. One Noble wit, who kept our morale up under fire, once stood at the shower door with his arm extended, and said, “You see ma, this is where we....” I do not recall what my parents thought of Noble Dorm, but my father was amused by the weekly practice of mailing laundry home; most dorm guys did this, and we had aluminum boxes made for the purpose. Dad noted, “at least we know that you are alright.”

The only Noble complaint that we dormers made was over the food. There were a series of protest meetings, and after each one the poor dietician would increase the meat supply, but she was obviously struggling with a budget, and up against guys away from mom’s cooking. She served us meals with names like “porcupine balls” and kept dink rules like wearing suits on Sundays, which resulted in some creative fashions in protest—like mixed coats and trousers. The Russian Revolution has been traced to discontent with a meal, so perhaps she gave us a rehearsal for the 1960s.

The entrance of one attractive woman in that “chow hall” would have spruced us up. But we were miles from the female enclave at Lincoln Avenue Residence (LAR) and I never saw coeds in Noble, although we guys might be bused to LAR. In all our Noble rowdiness nobody ever thought to smuggle in girls. We all maintained the medieval wall of separation between scholarship and courtship.

Once outside the dorm, cosmopolitan Bill Field and I lived the life of Holmes and Watson, with a Mrs. Allen in the role of Baker Street’s Mrs. Hudson. At semester’s end my merry roommates pledged Greek. I cannot imagine what coed dorms are like.

I have always opposed dink rules everywhere in life, but as an academic librarian I came to appreciate the stress I gave to those long ago administrators. A low point in my library career, in another institution, was when an art student set up an easel on a library table and began copying from a rare book with a water jar and open tubes of paint. I had to kick him out, and his work was beautiful. A high point was when a young woman in that institute made a film showing a bit of skin, and I hired her work in the school library—not without some grumbling from the old guard.

I wonder what became of “the girl with the golden arm.”

To think that in some darker time,

Love, sweet love, was thought a crime.

—Kipling

The views expressed in Storyography are not necessarily those of the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences or the University of Illinois.